The Crook

In which I discover my family's career criminal.

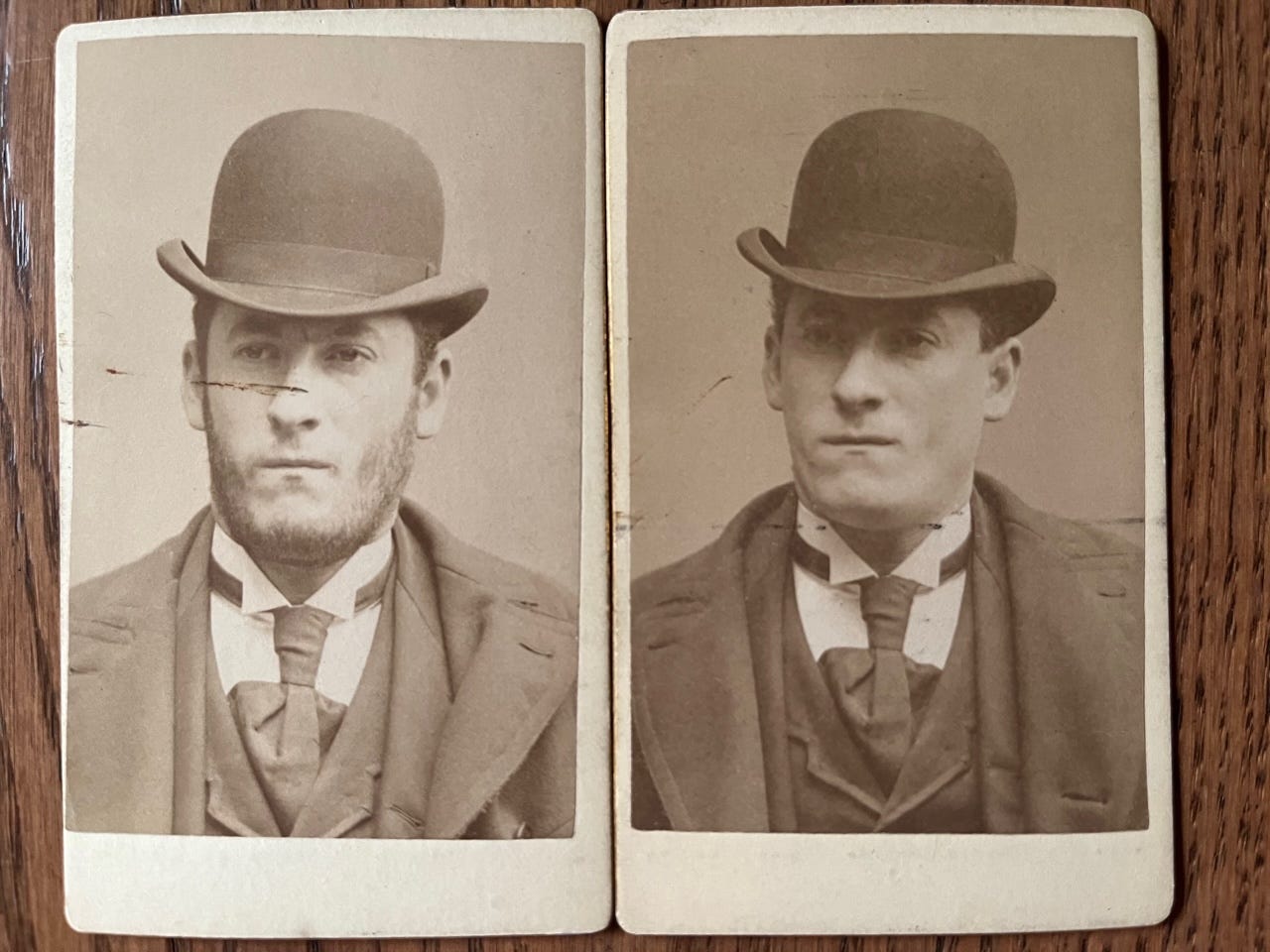

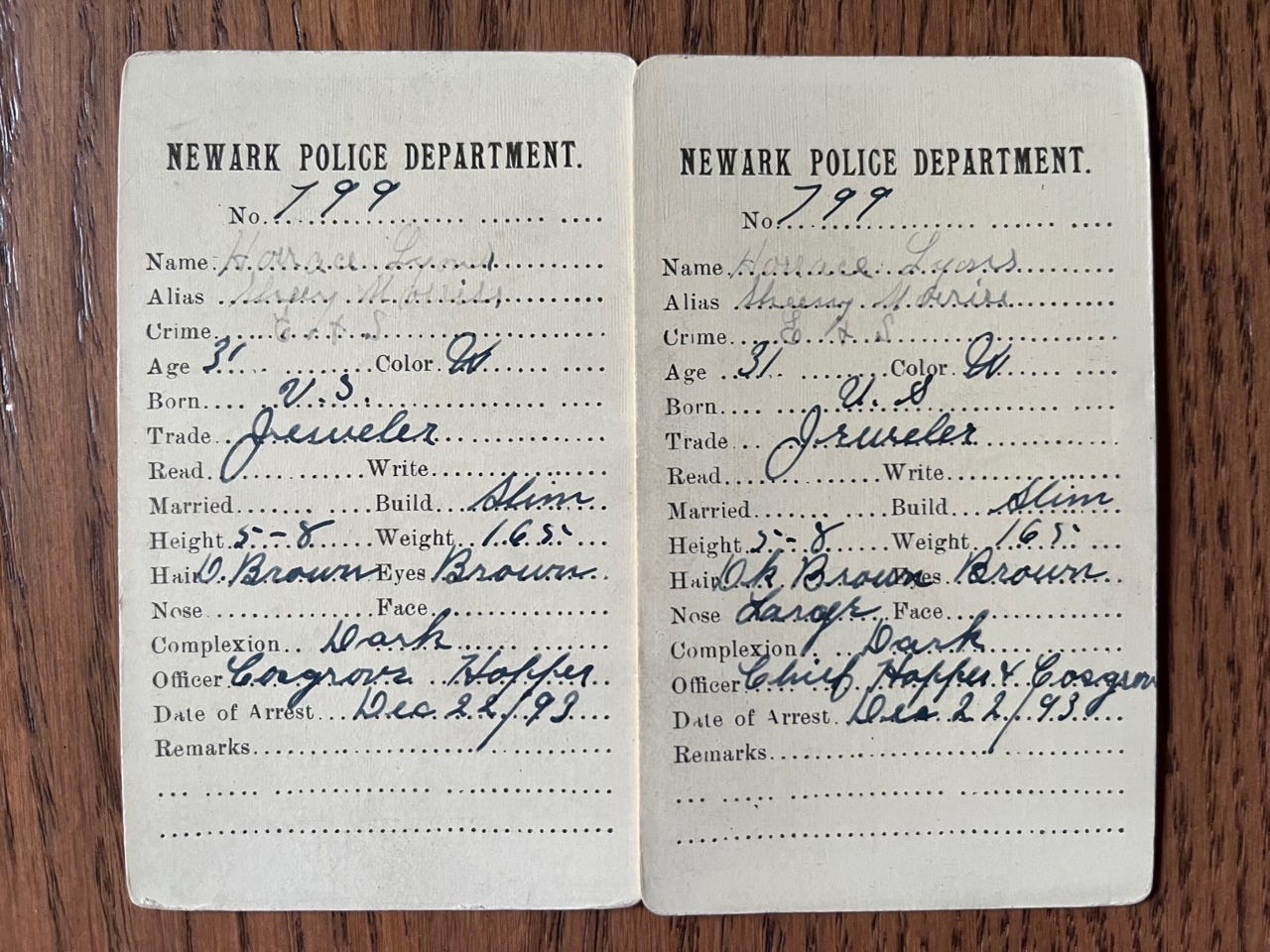

NOTE: I’ve added an exciting UPDATE at the end of this blog, which includes a mugshot!

My mother always maintained that her grandfather was a small-time bookie1 in downtown Newark, New Jersey, in the early years of the 20th century, and that he eventually lost everything in the gambling establishment that he ran. That’s why the house he and his wife bought in the then-upscale Vailsburg section of the city belonged solely to his wife, so that he couldn’t lose their home if his illicit activities went south. And he didn’t. Lose their home, that is. Only because it was his wife’s. Thank goodness. Because this home was where his four grandchildren — including my very own mother — were being raised.

I naturally found the idea of my great-grandfather’s career in illegal gambling rather fascinating and so, when I was finally able to access some pertinent newspaper archives online, I started searching for his name. Abraham Lyons of Newark, New Jersey. Surely, he’d been arrested at least once.

Only it wasn’t my great-grandfather’s name that I found. Not at all. It was that of his eldest brother, Harris Lyons.

Harris Lyons, the man also known during the course of his life as Horace Lyons, George H. Lyons, Thomas Lyons, John Raymond, Domenico Rocco, John Richmond, Henry Redwood, and William Smith.

How does a career criminal get his start? In 1870 Harris G. Lyons was an eight year-old kid living with his parents and siblings in lower Manhattan, swimming in the East River with his friends on hot summer days. In 1880, at age 18, he reported to the census taker that he was the proprietor of a newspaper stand. Five years later, at 23, he was making headlines in those same newspapers.

Harris Lyons went to prison for the first time — that I know of — after participating in the well-publicized 1885 theft of silver from the New York City home of Mrs. Schuyler Hamilton. Yes, the Schuyler Hamilton (Jr.) who was descended from Alexander Hamilton. Yes, the Hamilton family silver. But wait, it gets better. In the course of this investigation, it became known that the “fence” used to dispose of the Hamilton silver was a well-known New York City Alderman. My Great-Granduncle Harris was called to testify in the subsequent legal proceedings against the Alderman. I was amused to find that, in order to secure his testimony in court, Uncle Harris was spirited out of Sing Sing Prison to the local Manhattan jail in a very hush-hush operation … which was then duly speculated on quite openly by the newspapers.

He was sentenced to six years and six months for this 1885 crime, during which time his immigrant father died in Manhattan and his widowed mother went to live with one of his younger siblings. It was alleged in the papers that Harris was part of a larger group of thieves he’d been involved with for years in both New York and New Jersey. The physical description written down upon his admittance to prison makes note of some scarring on his face from old wounds, so the gang of thieves theory isn’t surprising.

Harris served the full six years and six months for the Hamilton silver heist, discharged from Sing Sing in 1891. He then went right back to prison in 1893 for burglary, this time in New Jersey. This arrest involved his extradition from Manhattan to Newark, New Jersey, where he was convicted of till tapping.2 The cop who arrested Harris in Manhattan got a commendation for rounding up the notorious Harris Lyons. The newspaper accounts called Harris a “well-known crook” — and not for the first or last time was that phrase used.

In 1901 Harris again ended up in Sing Sing Prison, this time for Grand Larceny. In the course of his confinement, he was transferred to Clinton Prison, where his sentence was commuted by 10 months. He was out in the public again in 1904.

Born and raised in lower Manhattan, Harris was the eldest of four children of European Jewish immigrants. His father, Samuel Lyons, came from what is now Poland, but which was very much under Russian rule in the early 19th century. The family lore holds that Samuel’s family was scattered in one of the many pogroms of that period, and that he made his way alone through Europe and then to the United States, arriving in 1854. I’m pretty confident about that 1854 date, based on immigration records, but that handed-down oral history about him has no proof so far. It’s true that Samuel did enter the U.S. alone and that his children did not know their Lyons grandparents. It’s true that his 1866 naturalization certificate states that he renounced all allegiance to the Emperor of Russia. But, as for the story about his traveling through Europe alone from a young age and then being wounded in the Crimean War (serving on the British side) — who knows?

Samuel Lyons was a jeweler in Manhattan. Was he honest? I don’t know. His three sons weren’t. Samuel’s naturalization record states that he had declared his intent to be naturalized in 1861 in Macon, Georgia. But in 1861, Georgia was no longer a part of the United States of America, and Samuel was a resident of Manhattan at that time3. Of course, no record of this Declaration of Intent can be found. But the Court in Manhattan seems to have taken his statement at face value, and Samuel was duly naturalized in 1866.

Back to Harris. Or Horace, as his name was frequently written, which gives rise to questions about the pronunciation of “Harris.” (I have no proof, but I’m willing to bet that the received pronunciation from his immigrant parents sounded a lot more like Horace than the name we would say as Harris.)

So, with Harris out of prison in 1904, we find in the 1905 New York State Census a likely entry for a “G. Lyons” in a very large boarding house or tenement in Manhattan. Given that the age is correct for Harris, that his middle initial actually is “G” and that one of his known aliases was “George H. Lyons,” I’m thinking this entry is probably him.

Now we come to something interesting: Harris, the well-known crook of both New York and New Jersey fame, managed to get a young woman to marry him. By 1908, Harris had moved on from Manhattan to Newark and had opened a stationery store on Market Street, in a building once used as a cigar store by his younger brother, Abraham. In 1910 Harris married Gertrude, a woman who was fully 25 years his junior. In 1911, they had a daughter. In 1913, Harris was once again under arrest.

Seems the stationary store in downtown Newark was a front for a very robust gambling operation. Although Abraham and Dan Lyons had some shady dealings, it was eldest brother Harris who was the big-time family bookie. The set up was this: The stationery store that opened onto the street was a legitimate business. Just behind the shop was a room of stock and sundry items, as would be expected in this kind of building. But in a third room at the very back of the building was the gambling operation: a room for poker and pool playing … and betting.

The spectacular 1913 raid that was pulled off by Essex County law enforcement saw Harris’s customers literally diving out of the windows in an effort to evade the police. But the building was surrounded, and thirty-eight men were rounded up. Most were let go, but four were charged with keeping a “disorderly house.” Harris and his youngest brother, Dan, were among those four men. Eventually, only Harris went to prison, Dan being let off after paying a hefty fine.

After changing his plea to guilty, Harris was sentenced to a term of one to four years. So far, I’ve found no record of the number of years he actually served for this crime; I do know that he was not at home for the 1915 New Jersey State Census, but the 1920 US Federal Census finds him in the household once again with Gertrude and their daughter. The 1913 arrest and subsequent conviction was his last, and he died at home in 1924.

Even in death, though, Harris remains a character of interest. His death certificate contains the name of his burial spot: Fairmount Cemetery in Newark, NJ. This is a cemetery I’m familiar with, but I had no idea Uncle Harris was in that same cemetery. Absent any online records such as a Find-a-Grave entry, it took a phone call to the cemetery office to get the juicy details about this particular grave site. Turns out it’s a very large plot in a very conspicuous spot in the center of the cemetery. Harris, his wife, Gertrude, and their daughter and son-in-law are buried there, along with numerous members of the family of Gertrude’s sister. What was so juicy about the whole thing is that the name of the plot owner is … “George H. Lyons.” At first, I thought there must be a mistake, because Harris is “Harris G. Lyons” and the “G” might have stood for George (I’ve no evidence so far of that). Maybe they just mixed it up. Harris G. Lyons. George H. Lyons. Simple mistake.

Well, turns out the cemetery records didn’t mix anything up. I took another look at the Newark City Directories and found one George H. Lyons, a confectioner, with a shop on Mulberry Street, and a home at the exact same address as … wait for it … Harris G. Lyons. This George Lyons is not enumerated in the 1920 census with Harris Lyons’ household, but, year after year, from 1916 to 1923, his City Directory entries are very clear as to the address where he ostensibly resided. Should we take bets that George H. Lyons’ confectionery store was the replacement front for Harris Lyons’ gambling operation, or other illegal activity, after his 1913 debacle?

I remain puzzled as to why Harris would feel the need to purchase a cemetery plot under an alias. A cemetery plot. And one located that prominently in the cemetery? Why not just purchase it in your wife’s name and be done with it?

But I think it’s all of a piece with his life of being a shady character who frequently played fast and loose with the truth.4

And Gertrude? She was just 35 years old when Harris died, and their daughter was 13. She kept on with the stationery/novelty store for several more years, apparently without a gambling operation attached to it. She married again a good 25 years after Harris died, moving with her second husband to the suburb of Glen Ridge. But she was duly buried beside Harris in the Fairmount Cemetery plot at her death in 1955.

Update Oct 30, 2023: a very kind genealogical researcher found, to my delight, that she was in possession of Harris’ mugshot from his 1893 arrest. Her specialty is vintage mugshots and crime stories, and her fascinating blog, Captured and Exposed, is found at capturedandexposed.com. Many thanks, Shayne Davidson! As you can see from the arrest record, Harris had yet another alias: Sheeny Morris. (According to Shayne, “Sheeny” was a slur often used then to refer to someone who was Jewish, which Harris was.

A slang term for bookmaker, a bookie is the person who facilitates gambling.

“Till tapping” was an old term for the theft of money from a cash register. Working with an accomplice who distracted the proprietress of the store, Harris robbed the cash register.

According to his 1860 US Federal Census entry.

One instance of many: the age he claimed to be on his 1910 marriage certificate was 42, but he was actually 46 or 47 years old at the time of the marriage.